Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)—also known as Bechterew’s disease—is a chronic, inflammatory form of arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints (where the spine meets the pelvis). Over time, inflammation causes stiffness and can lead to fusion of the vertebrae, resulting in reduced flexibility and a forward-stooped posture.

With modern treatments, the progression of AS can often be slowed or halted, allowing most patients to lead active, productive lives.

How Common It Is and Who Gets It? (Epidemiology)

Ankylosing spondylitis typically affects young adults between the ages of 15 and 45 and is more common in men than women. It tends to run in families and is strongly associated with the genetic marker HLA-B27. However, not everyone with this gene develops AS.

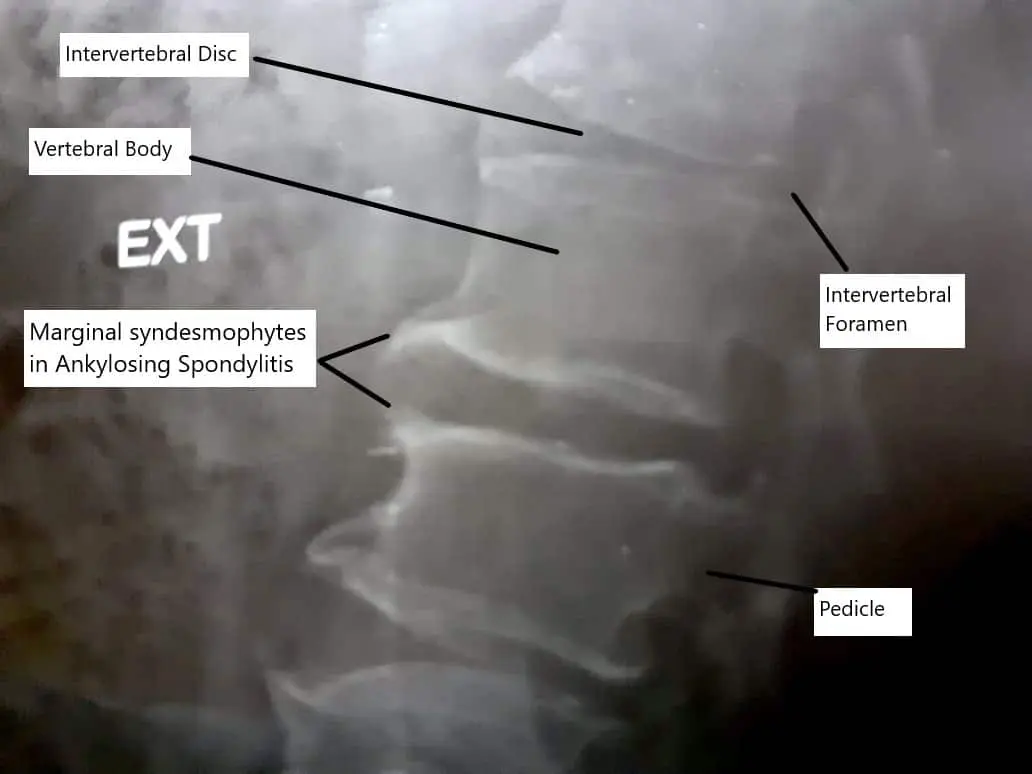

Syndesmophytes in Ankylosing Spondylitis

Why It Happens – Causes (Etiology and Pathophysiology)

The exact cause of AS is unknown, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic, autoimmune, and environmental factors.

- The immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own joints, particularly the areas where tendons and ligaments attach to bone (entheses).

- This causes inflammation, bone erosion, and eventual new bone formation, leading to fusion (ankylosis) of the joints.

- The disease most commonly begins in the sacroiliac joints, progressing upward to involve the spine and sometimes the hips, shoulders, or ribs.

How the Body Part Normally Works? (Relevant Anatomy)

The spine is made up of small bones called vertebrae, separated by flexible discs that allow movement. Facet joints connect these bones, and ligaments and tendons attach muscles to the spine.

In AS, chronic inflammation occurs at these attachment points. Over time, new bone growth bridges the joints, creating a rigid spine and limiting flexibility.

What You Might Feel – Symptoms (Clinical Presentation)

Common symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis include:

- Chronic low back pain that improves with activity and worsens with rest.

- Morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes.

- Pain in the buttocks or hips, especially alternating between sides.

- Fatigue and reduced flexibility in the spine.

- Stooped or hunched posture (kyphosis) as the disease progresses.

- Pain in the heel or chest due to inflammation where tendons attach.

- Inflammation of the eyes (uveitis): Redness, pain, or blurred vision.

In advanced cases, the entire spine may fuse, resulting in a forward-bent position (“chin-on-chest” deformity) and restricted lung expansion.

How Doctors Find the Problem? (Diagnosis and Imaging)

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical symptoms, lab tests, and imaging:

- Physical examination: Checks for spinal stiffness, limited movement, and chest expansion.

- Blood tests: Elevated ESR and CRP indicate inflammation; HLA-B27 confirms genetic association.

- X-rays: Show sacroiliac joint erosion, calcification, and syndesmophytes (bony bridges).

- MRI: Detects early inflammation in the sacroiliac joints before changes appear on X-ray.

- CT scans: Provide detailed views of bone fusion and deformities.

Classification

The Modified New York Criteria for diagnosing AS include:

- Radiological criteria: Bilateral sacroiliitis (grade ≥2) or unilateral (grade ≥3).

- Clinical criteria:

- Low back pain >3 months that improves with exercise but not rest.

- Limited motion of the lumbar spine.

- Reduced chest expansion.

AS is diagnosed when the radiologic and at least one clinical criterion are met.

Other Problems That Can Feel Similar (Differential Diagnosis)

- Mechanical low back pain

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)

- Spinal infections or fractures

Treatment Options

Non-Surgical Care

Medical management is the mainstay of treatment for ankylosing spondylitis.

- Medications:

- NSAIDs: First-line treatment for pain and inflammation.

- DMARDs (Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs): Such as sulfasalazine or methotrexate for peripheral joint involvement.

- Biologics (TNF or IL-17 inhibitors): For moderate to severe disease that doesn’t respond to other medications.

- Corticosteroids: Used short-term to control flares.

- Physical therapy and exercise:

- Stretching and posture exercises maintain flexibility.

- Deep breathing exercises improve lung capacity.

- Swimming and yoga help reduce stiffness.

- Lifestyle modifications:

- Maintain good posture.

- Avoid smoking—it worsens lung and spine symptoms.

- Maintain a healthy weight to reduce spinal stress.

Surgical Care

Surgery is considered when there is:

- Severe deformity or spinal fusion limiting vision and posture.

- Persistent pain unresponsive to medication.

- Nerve compression or fractures.

Common procedures include:

- Spinal osteotomy: Bone-cutting surgery to correct deformity.

- Spinal fusion with instrumentation: Stabilizes the spine and restores alignment.

- Joint replacement: For severe hip or shoulder involvement.

Recovery and What to Expect After Treatment

With medication and physical therapy, most patients experience significant pain relief and improved mobility.

After surgery, patients typically regain upright posture and enhanced breathing ability. Physical therapy continues postoperatively to maintain flexibility and prevent stiffness.

Possible Risks or Side Effects (Complications)

Complications can arise from the disease or its treatment:

- Spinal fractures from weakened bones.

- Severe spinal deformity (kyphosis).

- Eye inflammation (uveitis).

- Heart or lung complications from chronic inflammation.

- Medication side effects: Gastric irritation, infection risk, or liver toxicity.

Long-Term Outlook (Prognosis)

While there is no cure, modern therapies significantly slow disease progression. With consistent treatment, many patients maintain normal activity and spinal flexibility. Early diagnosis and active management improve long-term outcomes and reduce disability.

Out-of-Pocket Costs

Medicare

CPT Code 22800 – Spinal Fusion: $332.53

CPT Code 22212 – Osteotomy (Deformity Correction): $369.99

CPT Code 22842 – Instrumentation (Rods, Screws, Plates – 3–6 Segments): $185.26

Under Medicare, 80% of the approved amount for these procedures is covered once your annual deductible has been met. Patients are responsible for the remaining 20%. Supplemental insurance plans—such as Medigap, AARP, or Blue Cross Blue Shield—usually cover this remaining portion, meaning most patients have little to no out-of-pocket expenses for Medicare-approved spine surgeries. These supplemental plans coordinate directly with Medicare, ensuring complete coverage for complex spinal deformity correction procedures, including fusion, osteotomy, and instrumentation.

If you have secondary insurance—such as Employer-Based Plans, TRICARE, or Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—it acts as a secondary payer after Medicare has processed your claim. Once your deductible is satisfied, these secondary policies can cover any remaining coinsurance or residual balance. Most secondary plans have a small deductible, typically between $100 and $300, depending on your plan and whether the surgery is performed in-network.

Workers’ Compensation

If your spinal deformity or instability requiring correction developed from a workplace injury or repetitive strain, Workers’ Compensation will pay all related medical and surgical costs, including fusion, osteotomy, and hardware placement. You will not have any out-of-pocket costs under an approved Workers’ Compensation claim.

No-Fault Insurance

If your spinal deformity or instability was caused or aggravated by an automobile accident, No-Fault Insurance will cover all necessary surgical and hospital costs, including osteotomy, fusion, and instrumentation. The only potential charge may be a small deductible depending on your individual policy terms.

Example

Jonathan, a 65-year-old patient with spinal deformity and instability, underwent a spinal fusion (CPT 22800), osteotomy (CPT 22212), and instrumentation (CPT 22842) to restore spinal alignment. His Medicare out-of-pocket costs were $332.53, $369.99, and $185.26, respectively. Because he had supplemental insurance through Blue Cross Blue Shield, the remaining 20% not paid by Medicare was fully covered, leaving him with no out-of-pocket expense for his surgery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q. What is ankylosing spondylitis?

A. It is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints, leading to pain, stiffness, and, in some cases, spinal fusion.

Q. Who is most likely to get ankylosing spondylitis?

A. Young adults between 15 and 45 years old, especially men with the HLA-B27 genetic marker.

Q. Is ankylosing spondylitis curable?

A. No, but modern treatments—especially biologic medications—can slow or stop disease progression and greatly improve quality of life.

Q. Can exercise help ankylosing spondylitis?

A. Yes. Regular stretching and strengthening exercises improve flexibility, posture, and breathing capacity.

Summary and Takeaway

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory arthritis that causes stiffness, pain, and fusion of the spine. It most often affects young adults but can be managed effectively with early diagnosis and treatment. Modern biologic medications, physical therapy, and, when needed, surgery can significantly improve mobility and quality of life.

Clinical Insight & Recent Findings

A recent review provided an updated understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of ankylosing spondylitis (AS), emphasizing the interplay of genetic, immune, environmental, and hormonal factors. The study identified the HLA-B27 antigen as the principal genetic factor, present in over 80% of AS patients, and detailed how its misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum triggers inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB and IL-23/IL-17. Other genes, including ERAP1, RUNX3, and IL23R, further contribute to immune dysregulation by altering antigen processing and T-cell differentiation.

Environmental factors like gut dysbiosis, particularly the overgrowth of Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostridium species, were shown to activate innate immunity and intestinal IL-23 production, linking intestinal inflammation to joint disease. Mechanical stress at tendon and ligament insertion points (entheses) promotes local cytokine release and bone remodeling, while the IL-23/IL-17 axis drives both bone erosion and abnormal new bone formation.

The review also highlighted the roles of vitamin D deficiency and sex hormones in disease activity, noting a higher prevalence and severity in men. These insights suggest that AS results from a multifactorial immune imbalance and point to personalized, immune-targeted treatments as the future of disease management. (Study of pathogenic pathways in ankylosing spondylitis – See PubMed.)

Who Performs This Treatment? (Specialists and Team Involved)

Ankylosing spondylitis is managed by a team including orthopedic spine surgeons, rheumatologists, pain management specialists, and physical therapists working together to reduce inflammation and preserve mobility.

When to See a Specialist?

Consult a specialist if you experience:

- Chronic back pain that improves with activity but worsens at rest.

- Stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes in the morning.

- Reduced flexibility or difficulty standing upright.

- Eye redness or pain with blurred vision.

When to Go to the Emergency Room?

Seek immediate care if you develop:

- Sudden loss of mobility or severe back pain after minimal trauma.

- Vision changes or eye pain (possible uveitis).

- Loss of sensation or weakness in the legs.

What Recovery Really Looks Like?

With consistent treatment, most patients maintain near-normal spinal mobility and activity levels. After surgery, patients experience improved alignment and breathing, with rehabilitation continuing for several months.

What Happens If You Ignore It?

Untreated AS can lead to permanent spinal fusion, severe deformity, restricted breathing, and heart or eye complications. Early management prevents these outcomes.

How to Prevent It?

While AS cannot be prevented, early detection and treatment slow progression. Maintaining posture, exercising regularly, and avoiding smoking are key preventive measures.

Nutrition and Bone or Joint Health

A diet rich in calcium, vitamin D, and anti-inflammatory foods such as leafy greens and fish supports bone health. Maintaining a healthy weight reduces spinal strain.

Activity and Lifestyle Modifications

Engage in low-impact exercises like swimming, yoga, and walking to maintain flexibility. Focus on good posture and use ergonomic furniture. Avoid prolonged sitting and practice daily stretching.

Do you have more questions?

What are the early signs of Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Early signs of Ankylosing Spondylitis include chronic back pain and stiffness, particularly in the lower back and hips, that is worse in the morning or after periods of inactivity. Other early symptoms can include fatigue and pain in the shoulders, neck, or other joints.

How does Ankylosing Spondylitis affect daily activities?

AS can make daily activities challenging due to pain, stiffness, and reduced flexibility. Tasks that involve bending, lifting, or twisting can become difficult. Maintaining good posture and using ergonomic tools can help manage these challenges.

Are there any specific exercises recommended for people with AS?

Yes, exercises that improve flexibility, strength, and posture are beneficial. Swimming, yoga, and stretching exercises are particularly recommended. It’s important to work with a physical therapist to develop a personalized exercise plan.

Can diet influence the symptoms of AS?

While no specific diet has been proven to cure AS, maintaining a healthy, balanced diet can help manage symptoms. Foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as fish, and anti-inflammatory foods like fruits and vegetables, can be beneficial.

How does AS affect sleep, and what can be done to improve it?

AS can affect sleep due to pain and discomfort. Using a firm mattress, maintaining good sleep hygiene, and managing pain with medications or hot/cold therapy before bedtime can improve sleep quality.

What are the long-term effects of Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Long-term effects can include chronic pain, spinal fusion, reduced mobility, and a stooped posture. Complications such as uveitis, heart disease, and lung problems can also occur if the condition is not managed properly.

Can Ankylosing Spondylitis be misdiagnosed?

Yes, AS can be misdiagnosed, especially in its early stages, because its symptoms overlap with other types of back pain and arthritis. A thorough medical evaluation, including imaging and genetic tests, is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

Is there a genetic test for Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Yes, testing for the HLA-B27 gene can support the diagnosis of AS. However, having the HLA-B27 gene does not necessarily mean you will develop AS, and not all individuals with AS carry this gene.

What is the role of biologic medications in treating AS?

Biologic medications target specific components of the immune system to reduce inflammation. They are typically used when other treatments, like NSAIDs, are not effective. Examples include TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors

Can women get Ankylosing Spondylitis, and are their symptoms different from men’s?

Yes, women can get AS. While it is more common in men, women can experience similar symptoms, though they may have more peripheral joint involvement (like the knees and wrists) and less spinal fusion compared to men.

How often should someone with AS see their doctor?

Regular follow-ups with a rheumatologist or orthopedic specialist are important. The frequency of visits can vary based on the severity of symptoms and treatment plan, but typically, every 3-6 months is recommended.

Are there any surgical options for AS, and when are they considered?

Surgery is considered when there is severe joint damage, spinal deformities, or when conservative treatments fail to relieve symptoms. Procedures may include joint replacement or spinal surgery to correct severe deformities.

What lifestyle changes can help manage AS symptoms?

Regular exercise, maintaining good posture, quitting smoking, and managing stress can help manage AS symptoms. Additionally, following a healthy diet and maintaining a healthy weight are beneficial.

Can pregnancy affect Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Pregnancy can affect AS symptoms, with some women experiencing a decrease in symptoms while others may see an increase. It is important to work closely with healthcare providers to manage AS during pregnancy.

Is Ankylosing Spondylitis considered a disability?

AS can be considered a disability, particularly if it significantly impacts daily activities and work. Eligibility for disability benefits varies by country and specific criteria.

What advancements are being made in the treatment of AS?

Research is ongoing to better understand the genetic and environmental factors of AS. Advances in biologic medications and the development of new therapies targeting specific immune pathways are promising.

Can alternative therapies help with AS symptoms?

Some people find relief from alternative therapies such as acupuncture, massage, and chiropractic care. However, these should complement, not replace, conventional medical treatments.

How does AS affect mental health, and what can be done about it?

Chronic pain and disability from AS can lead to depression and anxiety. Mental health support through counseling, support groups, and medication can be important aspects of comprehensive care.

What is the prognosis for someone with AS?

The prognosis varies. With early diagnosis and proper management, many people with AS can lead productive lives. However, without treatment, AS can lead to severe complications and reduced quality of life

Can children develop Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Yes, AS can begin in childhood, a condition known as juvenile ankylosing spondylitis. Symptoms in children can include pain and stiffness in the spine and peripheral joints.

How does Ankylosing Spondylitis affect work life?

AS can affect work life by limiting mobility and causing chronic pain. Adjustments such as ergonomic workstations, flexible hours, and regular breaks can help manage symptoms.

Can physical therapy alone manage AS symptoms?

Physical therapy is a crucial part of managing AS, but it is usually combined with medications and other treatments for optimal management of symptoms.

What are the warning signs that AS is getting worse?

Worsening AS symptoms include increased pain and stiffness, reduced range of motion, new joint pain, eye redness or pain, and symptoms of heart or lung involvement. It’s important to report these to your doctor promptly.

Are there specific sleep positions that can help with AS pain?

Sleeping on your back with a firm mattress and avoiding pillows under your neck or knees can help maintain a neutral spine position. Some people also find relief by sleeping on their sides with a pillow between their knees.

How does stress impact Ankylosing Spondylitis?

Stress can exacerbate AS symptoms by increasing inflammation and pain sensitivity. Stress management techniques such as mindfulness, relaxation exercises, and physical activity can help reduce the impact of stress on AS.