Sciatica, also known as lumbar radiculopathy, refers to pain that travels along the path of the sciatic nerve, extending from the lower back down to the buttock, thigh, and leg. It occurs when one or more nerve roots in the lower spine (L4–S3) become compressed or irritated, often due to a herniated or degenerated disc.

This pain may be sharp, burning, or shooting, and is sometimes accompanied by tingling, numbness, or weakness in the affected leg. Although often alarming, most cases of sciatica resolve with conservative care.

How Common It Is and Who Gets It? (Epidemiology)

Sciatica affects about 10–40% of people at some point in their lives. It is most common between ages 30 and 60, when the discs are most vulnerable to herniation. Both men and women are equally affected, though it is slightly more frequent in individuals with physically demanding jobs or sedentary lifestyles.

Why It Happens – Causes (Etiology and Pathophysiology)

Sciatica develops when a nerve root in the lower spine becomes compressed, irritated, or inflamed.

Common causes include:

- Lumbar disc herniation: The most frequent cause of sciatica.

- Degenerative disc disease: Aging discs collapse, narrowing nerve pathways.

- Spinal stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal compresses the nerves.

- Spondylolisthesis: Slippage of one vertebra over another.

- Trauma or injury: May cause swelling or misalignment.

- Tumor or infection: Rarely, mass effect or inflammation can compress nerve roots.

The result is pain and neurological symptoms that follow the path of the affected nerve root.

How the Body Part Normally Works? (Relevant Anatomy)

The sciatic nerve is formed by nerve roots from the lower lumbar and sacral spine (L4–S3). It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch and travels down the back of the thigh, branching into smaller nerves that control movement and sensation in the legs and feet.

When a disc herniation or other spinal change compresses one of these roots, the resulting irritation causes the typical symptoms of sciatica.

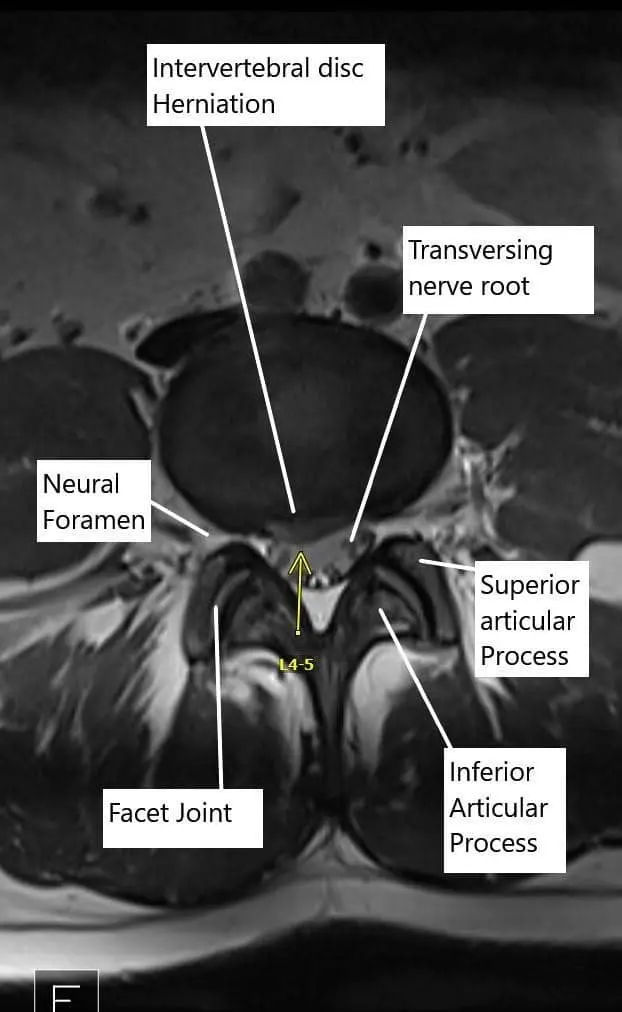

Axial section of the Lumbosacral MRI at L4-L5 level.

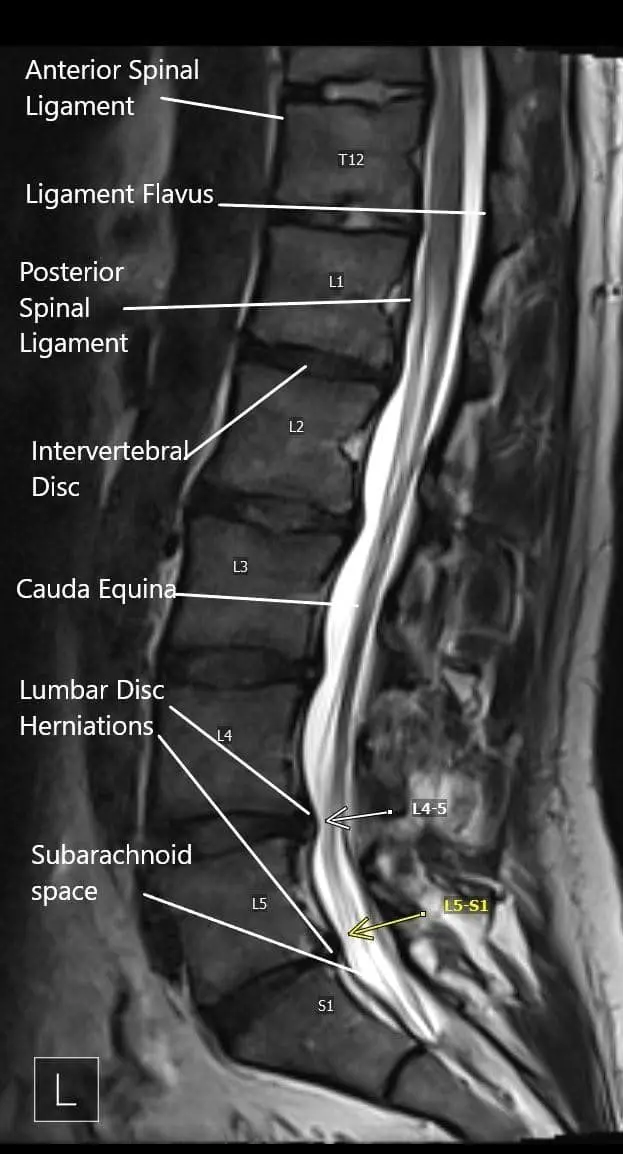

Sagittal section of the lumbosacral on MRI.

What You Might Feel – Symptoms (Clinical Presentation)

Symptoms depend on which nerve root is affected:

- L4 root: Pain or numbness along the inner leg; possible weakness in the thigh.

- L5 root: Pain radiating down the outer leg to the top of the foot; possible foot drop.

- S1 root: Pain down the back of the leg into the heel or sole of the foot; possible weakness pushing off the foot.

Other symptoms may include:

- Sharp, shooting pain radiating down one leg.

- Tingling or numbness in the leg or foot.

- Weakness when standing or walking.

- Pain that worsens with coughing, sneezing, or sitting for long periods.

- Rarely, loss of bladder or bowel control (a medical emergency called cauda equina syndrome).

How Doctors Find the Problem? (Diagnosis and Imaging)

Sciatica is primarily diagnosed based on symptoms and physical examination.

Diagnostic tools include:

- X-rays: To check spinal alignment or rule out fracture.

- MRI: The most accurate test to identify herniated discs or nerve compression.

- CT scan: Alternative imaging when MRI is not possible.

- Electromyography (EMG): Tests nerve and muscle function, especially if diabetes or other neuropathies are suspected.

Classification

Sciatica is classified based on duration and cause:

- Acute sciatica: Symptoms lasting less than 6 weeks.

- Chronic sciatica: Symptoms persisting beyond 12 weeks.

- By cause: Disc herniation, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, or other nerve compression.

Other Problems That Can Feel Similar (Differential Diagnosis)

Conditions that may mimic sciatica include:

- Hip arthritis or bursitis

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- Peripheral neuropathy (often from diabetes)

- Piriformis syndrome

- Vascular claudication

Treatment Options

Non-Surgical Care

Most patients (about 90%) recover without surgery. Initial treatment focuses on relieving pain and reducing inflammation:

- Medications:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Muscle relaxants

- Neuropathic pain medications (such as gabapentin)

- Physical therapy:

- Stretching and strengthening exercises for the back and core.

- Posture correction and gait training.

- Activity modification:

- Avoid prolonged sitting or heavy lifting.

- Maintain gentle movement and short walks.

- Epidural steroid injections:

- Deliver anti-inflammatory medication near the irritated nerve to reduce pain.

Surgical Care

Surgery is reserved for patients who fail conservative management or develop worsening neurological symptoms.

- Microdiscectomy: Removes herniated disc fragments pressing on the nerve.

- Laminectomy: Removes part of the bone or ligament causing nerve compression.

- Fusion surgery: Stabilizes the spine when instability contributes to nerve irritation.

Surgery is often minimally invasive, allowing for faster recovery.

Recovery and What to Expect After Treatment

- Non-surgical patients: Most recover within 4 to 6 weeks with therapy and medication.

- After surgery: Patients usually walk the same day or next day. Pain relief is often immediate, though numbness or weakness may take weeks to resolve.

- Rehabilitation: Strengthening and flexibility exercises help restore function and prevent recurrence.

Possible Risks or Side Effects (Complications)

- Persistent or recurrent pain

- Nerve injury or numbness

- Infection or bleeding (after surgery)

- Muscle weakness

- Scar tissue formation

These complications are uncommon and minimized with proper care.

Long-Term Outlook (Prognosis)

Most patients experience complete or near-complete recovery with conservative or surgical treatment. Pain relief occurs early, but recovery of strength or sensation may take longer. Early treatment of severe compression improves long-term outcomes.

Out-of-Pocket Costs

Medicare

CPT Code 63030 – Microdiscectomy (Removal of Herniated Disc): $225.06

CPT Code 63047 – Laminectomy (Decompression): $271.76

CPT Code 22612 – Fusion Surgery (Posterior Lumbar Fusion): $382.85

Under Medicare, 80% of the approved amount for these spine procedures is covered after the annual deductible has been met. The remaining 20% is typically the patient’s responsibility. Supplemental insurance plans—such as Medigap, AARP, or Blue Cross Blue Shield—usually cover this 20%, meaning that most patients have little to no out-of-pocket expenses for Medicare-approved surgeries. These supplemental plans work seamlessly with Medicare, ensuring that procedures like microdiscectomy, decompression, and fusion are fully covered.

If you have secondary insurance—such as Employer-Based coverage, TRICARE, or Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—it acts as a secondary payer once Medicare has processed the claim. After your deductible is satisfied, these plans often pay any remaining coinsurance or balance. Most secondary insurance policies carry a small deductible, generally between $100 and $300, depending on your policy and provider network.

Workers’ Compensation

If your lumbar radiculopathy was caused by a work-related injury or repetitive spinal strain, Workers’ Compensation will pay all related medical and surgical costs, including microdiscectomy, decompression, or fusion procedures. You will not have any out-of-pocket expenses under an accepted Workers’ Compensation claim.

No-Fault Insurance

If your lumbar radiculopathy developed or worsened as a result of an automobile accident, No-Fault Insurance will cover the entire cost of your medical and surgical care, including discectomy, laminectomy, or spinal fusion. The only possible charge would be a small deductible depending on your individual policy.

Example

Steven, a 59-year-old patient, underwent a lumbar microdiscectomy (CPT 63030) and posterior fusion (CPT 22612) to relieve leg pain and weakness from lumbar radiculopathy. His Medicare out-of-pocket costs were $225.06 and $382.85. Because he had supplemental coverage through AARP Medigap, the 20% not covered by Medicare was fully paid, leaving him with no out-of-pocket expense for the procedures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q. What causes sciatica?

A. Sciatica occurs when a lumbar nerve root is compressed or irritated, most often by a herniated disc or degenerative changes in the spine.

Q. Does sciatica go away on its own?

A. In most cases, yes. About 90% of patients recover with conservative treatment such as rest, therapy, and medication.

Q. When should surgery be considered?

A. Surgery is recommended if symptoms persist beyond 6 weeks, pain is severe, or if there’s progressive weakness or loss of bladder or bowel control.

Q. How long does recovery take after surgery?

A. Most patients return to normal activity within 3 to 6 weeks. Recovery may take longer for those undergoing fusion surgery.

Summary and Takeaway

Sciatica (lumbar radiculopathy) is a common condition caused by nerve root compression in the lower spine. It results in pain radiating down one leg, often with numbness or weakness. Most patients recover fully with conservative care, while those needing surgery also achieve excellent outcomes. Early evaluation ensures effective treatment and prevents complications.

Clinical Insight & Recent Findings

A recent randomized controlled trial protocol outlined the evaluation of ultrasound-guided acupotomy for treating lumbar radiculopathy with sciatica among active-duty military personnel. The study, conducted at the General Hospital of the Western Theater of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, will enroll 80 participants aged 18–45 with MRI-confirmed L4–S1 disc herniation and persistent sciatica for over three months.

Participants will be randomly assigned to receive either real or sham acupotomy once a week for four weeks. Primary outcomes include leg pain reduction measured by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and functional improvement using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

The trial aims to determine whether acupotomy, a minimally invasive procedure combining acupuncture and microsurgical decompression, can safely relieve pain and restore function within four weeks—addressing limitations of standard therapies like NSAIDs and physical therapy in military settings.

If effective, acupotomy could offer a rapid, non-surgical treatment option for sciatica, minimizing downtime and enhancing combat readiness. (Study of acupotomy for military training–induced lumbar radiculopathy with sciatica – See PubMed.)

Who Performs This Treatment? (Specialists and Team Involved)

Care for sciatica is provided by orthopedic spine surgeons, neurosurgeons, pain specialists, and physical therapists, working as a multidisciplinary team.

When to See a Specialist?

You should see a spine specialist if you experience:

- Persistent pain radiating down one leg for more than 4 weeks

- Weakness, tingling, or numbness in the leg or foot

- Pain that worsens with sitting or standing

When to Go to the Emergency Room?

Seek immediate care if you experience:

- Loss of bladder or bowel control

- Severe leg weakness or paralysis

- Numbness in the groin or inner thighs (saddle anesthesia)

What Recovery Really Looks Like?

Pain relief occurs first, followed by gradual improvement in strength and mobility. Most patients resume normal activities within 6 weeks. Ongoing stretching and strengthening exercises help prevent recurrence.

What Happens If You Ignore It?

Untreated sciatica can cause chronic pain, persistent weakness, or permanent nerve damage. Severe compression can result in cauda equina syndrome, requiring emergency surgery.

How to Prevent It?

- Maintain good posture and spinal alignment.

- Exercise regularly to strengthen the core and back muscles.

- Use proper lifting techniques.

- Avoid smoking and maintain a healthy weight.

Nutrition and Bone or Joint Health

A diet rich in calcium, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids supports bone and nerve health. Staying hydrated and reducing inflammatory foods help minimize back pain recurrence.

Activity and Lifestyle Modifications

Low-impact activities like walking, swimming, and yoga help maintain flexibility and core strength. Avoid long periods of sitting and take regular breaks during work or travel.