The sciatic nerve is the largest and longest nerve in the human body. It originates in the lower spine and extends down through the buttock and back of the leg, reaching all the way to the foot. Along its course, the nerve gives off multiple branches that supply muscles and carry sensory information from different regions of the leg. Compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve roots in the lower spine can result in pain radiating from the lower back down the leg, a condition known as sciatica.

Functional Anatomy

The sciatic nerve is formed by the union of five spinal nerve roots from the lower lumbar and upper sacral spine — specifically L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3. These roots exit the vertebral column through the neural foramina and merge to form the thick, rope-like sciatic nerve. At its widest point, the nerve measures about two centimeters in diameter.

The sciatic nerve is protected by a fatty sheath and receives blood supply through small vessels running along its surface, ensuring a constant flow of oxygen and nutrients to its fibers.

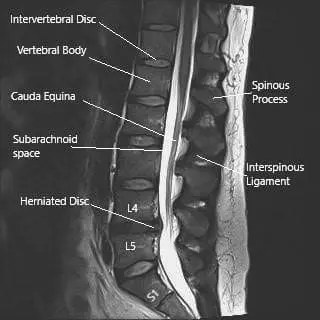

MRI image of the lumbosacral spine in sagittal section showing herniated intervertebral disc at L4-L5 level.

Sciatic Nerve Course

The Sciatic nerve exits the pelvis along with some blood vessels through the greater sciatic notch. The greater sciatic opening lies in the back of the pelvis under the piriformis muscle.

The nerve courses under the piriformis muscle and lies to rest on a small group of muscles responsible for external rotation of the hip joint. The nerve lies under the large buttock muscle (gluteus maximus).

The nerve after crossing the gluteus maximus enters the upper thigh and comes to lie under the large muscle in the back of the thigh (bicep femoris).

The nerve continues down the back of the thigh and divides into two branches in the back of the knee. The back of the knee joint known as the popliteal fossa is a conduit for various structures from the thigh to the lower leg.

The two divisions of the Sciatic nerve, the tibial nerve, and the common peroneal nerve continue down the leg. The tibial nerve continues in the back of the leg and supplies the calf and the soles of the feet.

The common peroneal nerve travels to the outer leg and the feet. The nerve divides into two branches, the deep peroneal nerve, and the superficial peroneal nerve. Together they supply the muscles in the front and the outer side of the leg.

Although the largest nerve, the Sciatic nerve throughout its course lies deep in the thigh and the buttock and cannot be felt on palpation.

Biomechanics or Physiology

The sciatic nerve enables coordinated motion and sensation in the lower limbs. It carries motor signals from the spinal cord to muscles, allowing movement, and returns sensory information from the skin and joints to the brain. Its dual functions — motor and sensory — make it essential for balance, walking, and maintaining stability.

When the nerve or its roots are compressed, stretched, or inflamed, the result is pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness radiating from the back through the buttock and down the leg.

Motor Function

The Sciatic nerve controls the major muscle groups in the thigh, leg, and feet. The muscle groups help the human body to perform activities such as walking, running, sitting, climbing stairs, etc.

The Sciatic nerve supplies the four hamstring muscles namely the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, bicep femoris – long head, and bicep femoris – short head. The Sciatic nerve also supplies a part of adductor magnus muscles.

The hamstring muscles help the body to bend the knee and coordinate activities such as walking, climbing stairs, etc.

The tibial division of the Sciatic nerve supplies the muscles of the calf. The muscles include gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus, flexor digitorum longus, and hallucis longus. Together these muscles help us to stand on our toes and move the toes down.

The peroneal part of the Sciatic nerve divides to supply the major muscles on the outer side and the front of the leg. The muscles include tibialis anterior, peroneus longus, peroneus brevis, extensor digitorum longus, and hallucis longus.

The muscles on the front and the side of the leg help us to move the foot and the toes up and outwards. The muscles of the calf and the front of the legs together function to help us to walk in a coordinated manner.

Besides the major muscles, both the tibial and the peroneal division supply a number of small muscles in the feet. The small muscles in the feet help us to walk with stability.

Sensory function

Besides the motor function, the Sciatic nerve carries sensory signals from the legs and feet through its branches. The sensation from the back of the leg (calf) and the outer sole is carried by the tibial nerve.

The sensory input from the front and the outer aspect of the leg is carried by the common peroneal division. The sensation from the top of the feet is carried by the superficial peroneal nerve, whereas the sensation from the 1st and the 2nd webspace is carried by the deep peroneal nerve.

Blood Supply

The blood supply of the nerve is vital in maintaining the Sciatic nerve’s function. The blood supply may be compromised in systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and in cases of external pressure over the nerve.

Common Variants and Anomalies

In most people, the sciatic nerve passes beneath the piriformis muscle in the buttock. However, in some cases, the nerve splits into two branches before exiting the pelvis, with one branch passing through or above the muscle. This variation, known as piriformis variant anatomy, can predispose individuals to piriformis syndrome, where the muscle irritates the nerve, causing sciatica-like pain.

Other anatomical variations include differences in the point where the nerve divides into its two terminal branches — the tibial and common peroneal nerves — which can occur anywhere between the upper thigh and the popliteal fossa (back of the knee).

Clinical Relevance

The sciatic nerve’s large size and long course make it particularly vulnerable to compression or injury. The most common cause of irritation is a herniated disc at the L4–L5 or L5–S1 levels, which can compress one or more of the contributing nerve roots. Other causes include spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, piriformis syndrome, and direct trauma.

Symptoms typically include shooting pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in one leg. In severe cases, loss of motor control in the foot or bladder and bowel symptoms may indicate significant nerve root compression requiring urgent evaluation.

Imaging Overview

MRI is the most effective imaging tool for assessing sciatic nerve pathology. It can detect disc herniations, spinal canal narrowing, and nerve root compression at the lumbosacral level. CT scans and electromyography (EMG) may also be used to identify bone-related causes or assess nerve function.

An MRI of the lumbosacral spine often reveals the source of compression — most commonly a herniated disc at the L4–L5 level pressing on one of the contributing nerve roots.

Associated Conditions

Common disorders involving the sciatic nerve include:

- Sciatica – radiating leg pain due to nerve root compression.

- Herniated lumbar disc – displacement of disc material pressing on the nerve root.

- Piriformis syndrome – muscle spasm or hypertrophy compressing the nerve in the buttock.

- Lumbar spinal stenosis – narrowing of the spinal canal affecting multiple nerve roots.

- Peripheral neuropathy – often due to diabetes or systemic illness affecting the nerve’s blood supply.

Surgical or Diagnostic Applications

When conservative treatments such as physical therapy, medication, and injections fail, surgical decompression may be necessary. Procedures such as lumbar microdiscectomy or laminotomy can relieve pressure on the compressed nerve roots.

Nerve conduction studies and EMG tests are valuable diagnostic tools to confirm nerve dysfunction, identify the level of involvement, and rule out other neuromuscular disorders.

Prevention and Maintenance

Good posture, regular exercise, and maintaining flexibility in the hips and lower back are key to preventing sciatic nerve compression. Strengthening the core and leg muscles helps support the spine and reduce stress on the nerve roots.

Avoiding prolonged sitting, lifting heavy objects improperly, and repetitive bending can also reduce the risk of sciatica. Patients with diabetes or vascular conditions should manage their blood sugar and circulation to protect nerve health.

Research Spotlight

A recent review in Frontiers in Neurology compared experimental models of sciatic nerve injury, including constriction, ligation, crush, and transection methods, to study nerve pain and regeneration. It found that combining stem cells, neurotrophic factors, and biodegradable scaffolds shows the greatest potential for restoring nerve function.

The authors emphasized that future research should integrate genetic and biomechanical approaches to enhance treatment translation for sciatic nerve injuries. (Study of sciatic nerve injury models and regenerative treatments – See PubMed.)

Summary and Key Takeaways

The sciatic nerve is the body’s main communication line between the lower spine and the legs. It controls most of the muscles in the thigh, leg, and foot, and carries sensations from these areas to the brain.

Compression or irritation of this nerve can result in sciatica, a painful condition characterized by radiating leg pain. Proper diagnosis through imaging and physical examination is essential for effective treatment. Maintaining spinal flexibility, posture, and overall nerve health helps prevent recurrence and long-term disability.

Do you have more questions?

What side is sciatic nerve on?

Sciatic nerve is on either side of the lower back. It is from the base of the lower back on both sides and runs through the pelvis along the back of the hip joint and thigh on both sides.

Can the sciatic nerve be removed?

Sciatic nerve is a very important and one of the thickest nerves of the body. It is important for supplying motor function to the muscles of the leg and foot as well as taking sensations from the foot to the brain. Their critical function cannot be replaced by any other nerve or muscle. Thereby, it is important that the sciatic nerve is functional and present. Very rarely, patients may have tumor involving the sciatic nerve, which may have to be excised and may lead to sacrifice of the sciatic nerve; unless otherwise, the sciatic nerve is never removed due to its critical function.

What kind of doctors treat sciatica?

Sciatica can be treated by multiple types of doctors including primary care doctor, pain physician, sports physician, spine surgeons and orthopedic surgeons among others. The methodology to treat sciatica nonoperatively is essentially the same among all field. Operative treatment for sciatica can be done by an orthopedic surgeon or a spine surgeon or neurosurgeon.

Is sciatica permanent?

Sciatica is not permanent, though it can be a recurrent. Patients who have had one episode of sciatica are at a higher risk of getting recurrence over the period of months and years. If the patient gets relieved with recurrent episodes of sciatica in shorter duration of time then it can be still treated nonoperatively. Patient who have recurrent or prolonged episodes of sciatica, not relieved medications and physical therapy or patients who have neurological deficit or worsening pain, may need surgical treatment.

Can sciatica hurt in the front of thigh?

Sciatica or lumbar radiculopathy involving the L2, L3 and L4 nerve roots present as pain along the front of the thigh. The pain caused by pinching of the L2 and L3 nerve roots are present with pain along the upper and the middle thigh and may be associated with tingling and numbness. Pain due to the pinching of the L4 nerve root causes pain along the front of the lower thigh as well as over the knee and may have radiation into the inner leg.

Can sciatica affect nerve function?

In severe form of sciatica presenting with an emergency condition called cauda equina syndrome, in which there is severe compression with almost loss of all function of the nerve root, the patient may present with weakness of either or both lower extremities with or without involvement of bowel and bladder. Most of such patients will have loss of rectal tone leading to incontinence and loss of control of falls.

What does sciatic nerve innervate?

Sciatica nerve innervates all the muscles of the leg below the knee joint as well as carries sensations from the skin of the leg and foot. It also supplies all the muscles of the foot and is crucial in ambulating.

Can sciatica cause muscle loss?

Sciatica pain or radiculopathy can be associated with decreased motor innervation to the muscles leading to weakness. This will also lead to muscle atrophy over the long run.

Can you get sciatica in the arms?

The upper extremity equivalent of sciatica is called cervical radiculopathy. The process is similar to sciatica. The nerve root in the neck or the cervical spine is inflamed and irritated most commonly due to disk herniation in the neck. This leads to radicular pain along the arm and the forearm and to the hand depending on the nerve root, which is compressed or irritated.

Can sciatica nerve damage cause foot drop

Sciatica damage to L5 nerve root and S1 nerve root maybe associated with ankle weakness and occasionally foot drop. Such patients usually have a severe form of nerve damage. Treatment could include management of the radiculopathy, medications, physical therapy with or without surgery. Surgery may be more often needed in such patients especially if the neurological deficit is still evolving, so as to decrease or elevate the further neurological deficit as well as to optimize the recovery.